Introduction

For generations, from the ratification of the partition plan to the signing of Camp David and then the Oslo Accords, the world has sat with bated breath, waiting and expecting a permanent, sustainable solution to the Israel-Palestine conflict.

It goes without saying that in an ideal world, and historically in the wishes of most people involved, that settlement would have been reached long ago to allow Israelis and Palestinians to both live in peace and security on their terms. However, the nature of the conflict, the deeply entrenched positions, the politicking on both sides and the unabating threats to Israel’s security have made this prospect increasingly distant.

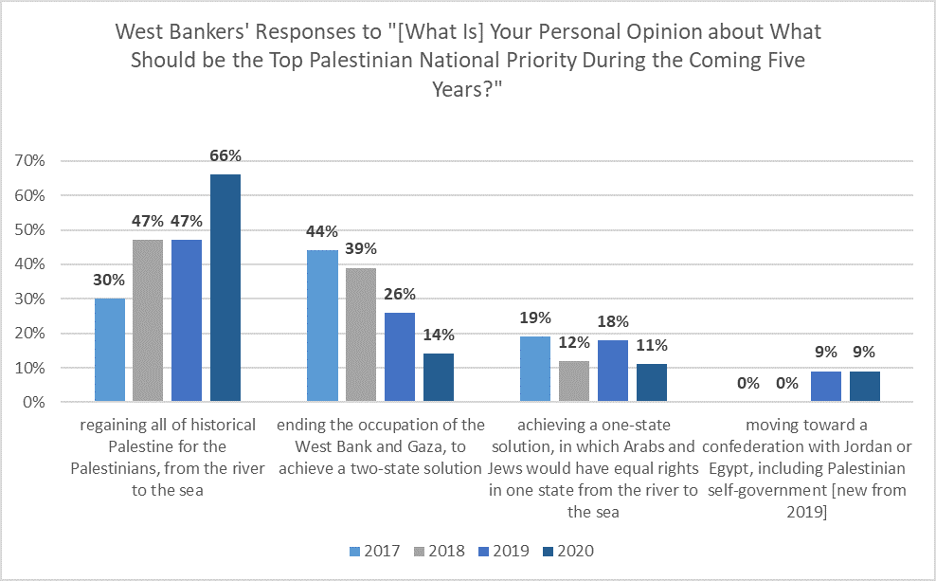

The realities on the ground are stark. The notion of a two-state solution, once more widely supported, has lost favour among Palestinians. Ironically, while some might think Palestinians reject recent peace plans due to limitations on the traditional two-state model, most Palestinian respondents in the West Bank, 66% in 2020, up from 30% in 2017, now reject that model entirely, envisioning only more armed struggle towards the goal of a singular Palestinian state and the eradication of Israel1.

The shift in Palestinian attitudes colours the landscape for those seeking a resolution to the conflict, and post-October 7th, those attitudes have taken on lethal consequences, and prospects for would-be peacemakers have become far bleaker.

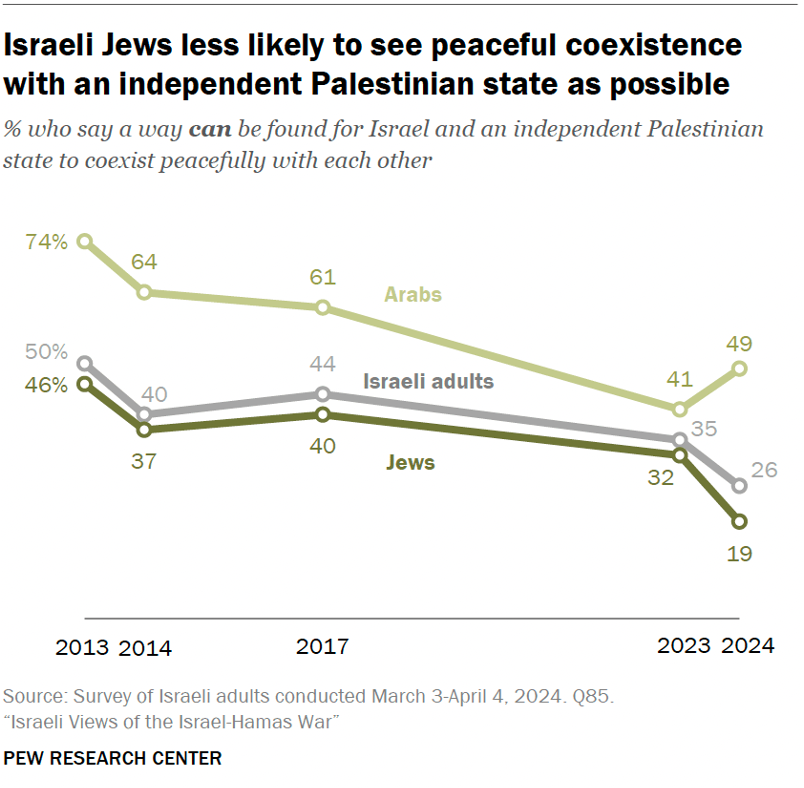

Many Israelis (74%), including 51% of Israeli Arabs, can see no path towards peaceful coexistence with a state influenced or run by Hamas in the face of the atrocity that left over 1,200 dead.2

The shift in Palestinian attitudes and their acceptance and perpetration of extreme violence towards those ends presents a challenging landscape for those seeking a resolution to the conflict. Israel finds itself in a seemingly impossible situation – establishing a Palestinian state right now could be disastrous, yet remaining in the territories indefinitely has forced Israel to put its citizens at constant risk and caused pressure and angst from a war-weary West.

So, what’s the way forward? Some argue for abandoning comprehensive peace plans and focusing instead on “shrinking the conflict” by improving Palestinians’ daily lives while maintaining Israel’s security. This approach recognises the current impracticality of a one-state solution, the return of refugees, or armed struggle against Israel.

For Israelis, it’s crucial to understand that any discussion of Israel’s future must prioritise its character as a Jewish and democratic state, but this has never precluded them from acceptance in theory of a peaceful Palestinian state alongside it.

Even Israeli leaders who’ve expressed scepticism about Palestinian statehood in the past have maintained support for a demilitarised Palestinian state alongside Israel.

However, the situation in Gaza complicates matters further. The idea of recognising Gaza as the Palestinian state, with no plan to extend it to the West Bank, has been floated. But with Hamas controlling Gaza and committed to Israel’s destruction, this approach raises serious security concerns.

Ultimately, Israel’s leaders face a delicate balancing act. They must navigate between the need for security, the desire for peace, and the realities of the situation. As the then-Israeli Defence Minister Avigdor Liberman stated in 2018, Israel may have “exhausted all options” regarding Gaza, speaking of the diplomatic stalemate that existed before the exchange of fire between Israel and Hamas in 2019.3

Since October 7th and Israel’s ground response to eliminate the perpetrators, this process seems ever more remote, while the International calls for a bilateral ceasefire have only got louder.

A bilateral ceasefire might seem to offer temporary respite. Still, while Hamas holds sway in Gaza and in the West Bank (as many commentators in the West do not seem to address), There is no prospect of guaranteeing Israel’s right to security through a two-state solution.

While still supported by some, the two-state solution faces significant challenges in its implementation. The path forward will require creativity, compromise, and an unwavering commitment internationally to Israel’s security and its legitimacy as a liberal democracy in the face of staunch opposition frequently framed in bad faith.4

Offers of Peace

Peel

Historically, the Palestinians have been offered statehood many times, beginning before the state of Israel existed in 1937,5 with the findings of the British Peel Commission, the Palestinians were offered 80% of the mandate, with a small Jewish state of 20% proposed. The Palestinian leader of the time, the Grand Mufti, made clear he had no intention of accepting any Jewish polity at all:

“Most residents of Jewish lands will not be awarded citizenship in our future country.”6

“The Mufti suggested that the Jews be deported from Palestine. Rejecting the idea of a Jewish state, he promised that if such a state were established, every Jew would be expelled from a Palestinian Arab state.7“

he said this as he continued his campaign of lethal riots against the Jews living in the mandate and the British themselves.

Partition

This entrenched attitude would remain ten years later when the Peel Commission had evolved into the UN partition plan. Again, providing for a larger Arab state and a smaller Jewish state on far less fertile land, Jerusalem was to be an international protectorate; still, the Palestinian leadership rejected the partition, with the surrounding Arab states starting the war, which they hoped would destroy the nascent Jewish state entirely.

Camp David Summit

Since the turn of the millennium, Israel has made multiple substantive offers to the Palestinian Leadership for true statehood8. In contrast, successive Palestinian leaders have rejected these offers.

In 2000, at Camp David, Ehud Barak offered the Palestinians statehood in approximately 92% of the West Bank and all of Gaza, with a capital in Jerusalem. The Palestinian Authority under Yasser Arafat rejected this offer.910 launching the murderous “Al Aqsa Intifada” that left 1,184 Israelis dead in suicide bombings and other acts of terror. Despite this, in 2001, Israel increased the offer to 97% of the West Bank, but it was again denied11.

Withdrawal from Gaza

Having entirely withdrawn from Gaza in 2005, In 2008, Israel, then led by Ehud Olmert, made an even more comprehensive offer12 that was rejected out of hand by Palestinian leaders. These rejections of genuine statehood offers contradict the claim made by some commentators that Israel has been unwilling to negotiate in good faith.1314

Settlements Moratorium

In 2009, under pressure from President Obama, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu agreed to a 10-month freeze on new settlement construction in the West Bank as a gesture to encourage the Palestinians to return to negotiations.15 Despite this significant concession, a major step that no previous Israeli government had taken, the Palestinian Authority, led by Mahmoud Abbas, only engaged in direct talks in the final weeks of the moratorium, leading to failure, blame and recrimination and16 demonstrating the reluctance of the Palestinian side to engage in talks, even when their preconditions were met.17

The “Trump” Plan

In 2020, the US-brokered “Peace to Prosperity” plan, also known as the “Trump Peace Plan”18 was unveiled in January 2020. This plan proposed a solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict by offering a pathway to Palestinian statehood19. Before seeing the details, Abbas rejected the US peace plan without a counterproposal, claiming it was too biased towards the Israelis. This consistent pattern of blanket rejection without genuine engagement demonstrates the unwillingness of the Palestinian leadership to negotiate pragmatically, underscoring that survey from the introduction and the 66% of Palestinians that would see Israel eradicated as a long-term goal.

The History of the Peace Process

The peace process has been a complex and often frustrating endeavour spanning decades, with setbacks and missed opportunities on both sides. Many remember Yitzhak Rabin, the Israeli Prime Minister assassinated in 1995 by an Israeli right-wing extremist opposed to his signing and attempted implementation of the Oslo Accords with the PLO in the preceding two years.20 Many see Rabin’s death as the beginning of the end of the two-state process envisioned at Oslo, even as between then and October 7th it was the ideal of the international community.

Before Camp David and the offers of Statehood, Israel made several substantive offers for peace with both the Palestinians and its Arab neighbours that, while providing glimmers of hope, were rejected by the Palestinian leadership. The process has been marked by periods of progress followed by outbreaks of violence, making sustained negotiations challenging.

The Camp David Accords

The 1978 Camp David Accords, brokered by US President Jimmy Carter between Anwar Sadat of Egypt and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin, were a significant milestone focusing on negotiations between Israel and Egypt and the basis for normalising relations between the two countries. In return for the Sinai, which Israel returned to Egypt following its capture during the six-day war, the two countries would mutually recognise and relate to each other diplomatically. The agreement marked the first rapprochement between Israel and an Arab state.21

Begin proposed, as a result, the possibility of Palestinian autonomy in a step towards addressing Palestinian self-governance within the complex realities of the time. The accords laid the groundwork for future negotiations and the scene setting for the Oslo Accords, though at the time, aPalestinian state had become a distant prospect.

The Oslo Accords

In 1993, Yitzchak Rabin and Yasser Arafat signed the Oslo Accords, agreeing to the principles of peace that could have led to a Palestinian state.

“The Oslo agreement was possible because of a tradeoff,” Dr. Ghassan Khatib, a former member of the Palestinian delegation to the Oslo meetings in Washington, told The Media Line. “The Palestinian side gave up the insistence that Israel stop the expansion of the settlements, in return for Israel giving a concession recognizing the Palestinian Liberation Authority (PLO): being willing to negotiate directly with PLO and allow the PLO to be the signatory of future agreement and the leadership of the Palestinian Authority.”22

Many analysts argue that the Oslo Accords were doomed due to fundamental flaws. One of the biggest criticisms is that Israel negotiated with the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), which some viewed as a terrorist organisation. This decision led to scepticism about the peace process’s legitimacy.

Critics also point out that the accords did not address key issues like the recognition of Israel as a Jewish state, which later contributed to continued violence and a lack of trust between the parties involved.23

As we discussed Rabin’s assassination by an Israeli extremist in 1995 dealt a significant blow to the peace process, and subsequent Israeli leadership, such as Benjamin Netanyahu, shifted away from Oslo’s principles, leading to a further breakdown in the peace process.

Bilateral Ceasefire Post-October 7th

The Nature of the Conflict and Asymmetry

On October 7th, 2023, Hamas, a designated terrorist organisation by many countries, launched a coordinated and unprecedented attack on Israel, killing over 1,200 civilians, including women and children, and taking others hostage.2425

This act was not an isolated incident but part of a broader strategy rooted in Hamas’ ideology, which openly calls for the destruction of Israel and the extermination of Jews. In this context, any response by Israel is not merely an act of defence but a necessary measure to ensure its survival against an enemy committed to its destruction.

Many in the West, in the immediate aftermath of this attack, called, some might say, reflexively for restraint and ceasefire on Israel before its actual response and while the perpetrators were still skirmishing with the IDF in Israel proper.

In such an asymmetric conflict, where one side is a democratic state defending its citizens and the other is a terrorist organisation in control of militarised territory and driven by genocidal intent, calls for a bilateral ceasefire are not as humanitarian as they appear. A ceasefire under these circumstances would effectively reward Hamas for its attack and allow it to rearm again in a fibral atmosphere, plotting to repeat the attack again and again. This, in turn, put the very existence of Israel and the lives of its citizens at continued risk.

Historical Context and Genocide Apologism

Hamas’ charter, since its inception, has included language that is explicitly antisemitic and genocidal; although toned down in a recent revision, the actions of Hamas clearly still adhere to the original:

“Hamas rejects any alternative to the full and complete liberation of Palestine, from the river to the sea…26

Jihad is its path and death for the sake of Allah is the loftiest of its wishes…

It is the duty of the followers of other religions to stop disputing the sovereignty of Islam in this region, because the day these followers should take over there will be nothing but carnage, displacement and terror…

Initiatives, proposals and international conferences are all a waste of time and vain endeavors. The Palestinian people know better than to consent to having their future, rights and fate toyed with”27

Hamas does not seek peace or coexistence but rather the complete destruction of Israel. In this light, any call for a ceasefire that does not also address the need to dismantle such a genocidal entity can be viewed as apologising for or downplaying the severity of Hamas’ intentions.

Those advocating for a ceasefire often frame their arguments in humanitarian terms, emphasising the need to prevent further loss of life. However, this perspective can be seen as ignoring the reality that Hamas’ tactics deliberately involve using civilian populations as human shields, embedding military operations within densely populated areas to provoke precisely the kind of response that then fuels international condemnation of Israel. By calling for a ceasefire without addressing Hamas’ actions, advocates may unwittingly be supporting a status quo that enables continued genocidal aspirations against Israel.

Humanitarianism as a Facade

The language of humanitarianism used in calls for a bilateral ceasefire often fails to recognise the inherent injustice of equating the actions of a legitimate state defending itself with those of a terrorist organisation. This false equivalence can be seen as a moral failure, where the genuine humanitarian justified concern for the loss of innocent lives is manipulated to serve a political agenda that undermines Israel’s right to the safety of its citizens within its borders.28

These calls ignore the broader humanitarian implications for Israeli civilians who have been subjected to terror and for whom a ceasefire that leaves Hamas’ capabilities intact does not bring peace but merely a temporary lull in an ongoing existential threat. The long-term humanitarian solution lies not in a superficial ceasefire but in the eradication of the root cause of the conflict—Hamas’ genocidal ideology.

Conclusion

In conclusion, while the call for a bilateral ceasefire might appear to be a neutral, humanitarian plea, the real implications of doing so while Hamas still has control in Gaza are to reward terrorism and treat Israel’s existence and sovereignty with contempt.

By not addressing Hamas and only Israel, such calls have bolstered Hamas’s continued violence and genocidal aspirations, effectively becoming genocide apologism masquerading as humanitarianism. True humanitarianism should seek to protect all lives, but it must also recognise the moral imperative to confront and dismantle the structures that perpetuate violence and genocide.

Peace

This is not to say that peace is not the overriding objective of most Israelis and many moderate Palestinians. Still, peace must be structural, sustainable, and committed to in general terms by both sides and a shared agreed-upon and popular framework.

The events since Oslo have made such a meeting of minds ever more remote

Palestinian experts themselves seem to feel we have gone beyond the paradigm of Oslo that the two-state solution is no longer attainable or desirable for the Palestinians themselves:

“What is clear to me is that this is the end of whatever chapter came before; call it the Oslo Accords chapter, the peace process chapter, or the two-state solution chapter. That paradigm is over. Now we must ask, “What is the next stage of the Palestinian struggle?”” – Khaled Elgindy, professor of Arab Studies at Georgetown University29

Post-October 7th, it is hard to see how a ceasefire, or continued conflict, will result in peace. While Palestinians refuse to engage meaningfully with Israel and cling to the notion of grand victory from the river to the sea, and while Israeli settlers in the West Bank enflame tensions and prevent

constructive dialogue, meaningful negotiations remain unattainable.

1. https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/palestinian-majority-rejects-two-state-solution-backs-tactical-compromises ↩

2. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2024/05/30/assessing-the-future-in-light-of-the-war/ ↩

3. https://www.timesofisrael.com/liveblog_entry/liberman-on-gaza-weve-exhausted-all-options-time-for-the-army-to-go-in/ ↩

4. https://www.jpost.com/israel-news/article-811987 ↩

5. https://besacenter.org/palestinian-rejectionism/ ↩

6. ibid ↩

7. ibid ↩

8. https://lawandsocietymagazine.com/how-palestine-rejected-offer-to-have-its-own-state-5-times-in-the-past/ ↩

9. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2000_Camp_David_Summit ↩

10. https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/background-and-overview-of-2000-camp-david-summit ↩

11. https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/camp-david-two-years-later-what-might-have-been ↩

12. https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/unlikely-peace-prospects-israeli-palestinian-agreement-2008 ↩

13. https://www.middleeasteye.net/opinion/israel-palestine-negotiation-idea-always-fiction (bad faith narrative) ↩

14. https://www.thenation.com/article/society/letters-from-the-june-1-8-2020-issue/#:~:text=Chomsky%20cites%20an,peace%20is%20astonishing. ↩

15. https://www.voanews.com/a/us-welcomes-israeli-settlement-move-urges-palestinians-to-enter-negotiations-73905167/415919.html ↩

16. https://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/11/world/middleeast/11diplo.html ↩

17. https://edition.cnn.com/2009/WORLD/meast/11/25/israel.settlements/index.html ↩

18. https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/peacetoprosperity/political/ ↩

19. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/trumps-economic-proposal-is-an-opportunity-in-disguise/ ↩

20. https://education.cfr.org/learn/timeline/israeli-palestinian-conflict-timeline ↩

21. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Camp_David_Accords ↩

22. https://themedialine.org/top-stories/30-years-later-oslos-failures-haunt-both-sides/ ↩

23. https://www.timesofisrael.com/why-the-oslo-peace-process-failed-and-what-it-means-for-future-negotiators/ ↩

24. https://www.hrw.org/news/2024/07/17/october-7-crimes-against-humanity-war-crimes-hamas-led-groups ↩

25. https://www.hrw.org/report/2024/07/17/i-cant-erase-all-blood-my-mind/palestinian-armed-groups-october-7-assault-israel ↩

26. https://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/hamas.asp ↩

27. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/doctrine-hamas ↩

28. https://www.jewishpress.com/indepth/opinions/when-neutrality-is-immoral-israel-hamas-and-the-problem-of-moral-equivalence/2023/11/26/ ↩

29. https://gjia.georgetown.edu/2023/11/09/thinking-through-the-diplomatic-strategic-and-humanitarian-implications-of-the-israel-hamas-war-with-expert-of-palestinian-affairs-khaled-elgindy/ ↩

Leave a Reply