Introduction

The establishment of Israel in 1948 was never, as so frequently framed, simply a response to the Holocaust. Or, indeed, a European colonial enterprise. Instead, Israel and the notion of Zionism can be viewed as the culmination of a clear line of Jewish history stretching back to the Iron Age.

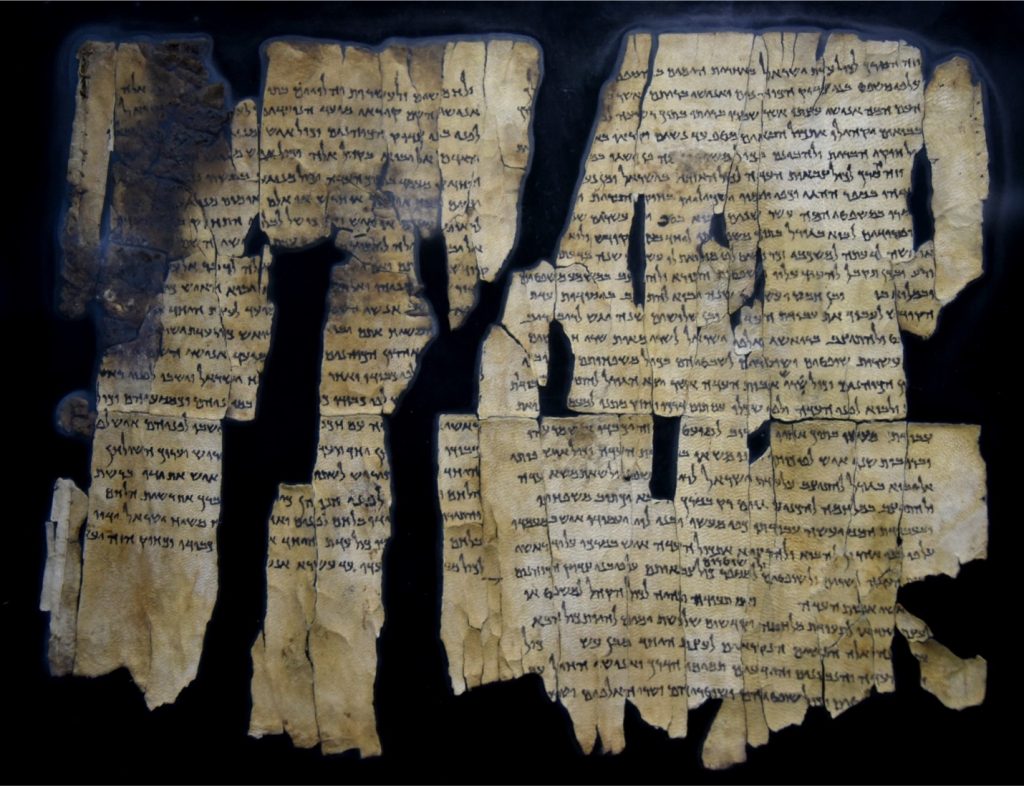

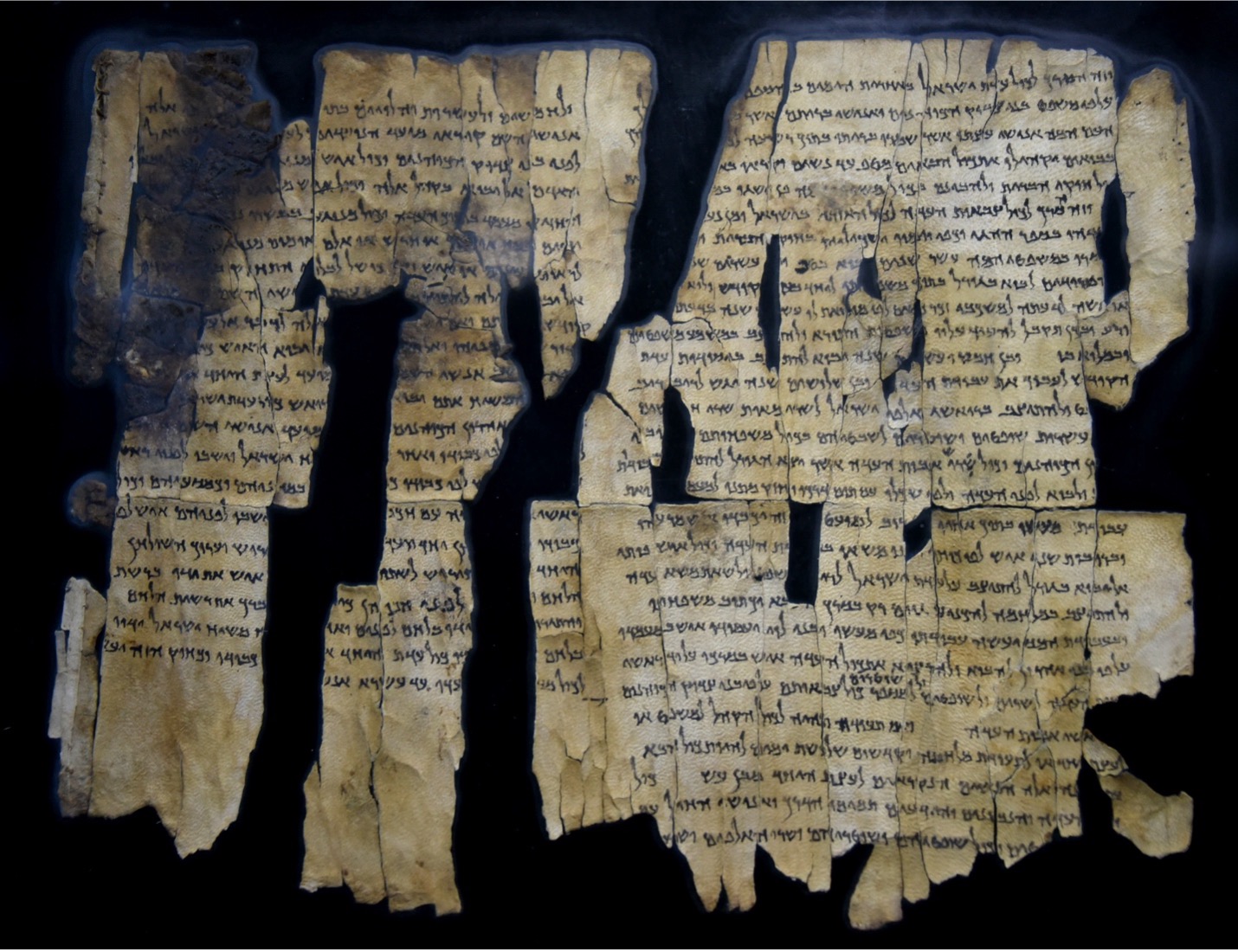

The stories of the Torah might be mythological, with the early books consisting of what most would call a founding myth. Still, these narratives are undeniably ancient, proof, especially through the ancient biblical texts found in the Dead Sea Scrolls1, of their age, the people that revered them, the place where they did so and the area where the stories were written. That place was roughly the same as the modern-day State of Israel; those people were the Israelites who became the Jewish people.

This is why Jewish people, quite apart from sharing a common Levantine genetic heritage, also share a sense of belonging to the nation of Israel, that is, of being one people, one extended family or tribe. The State of Israel represents the fulfilment of a long-standing aspiration for Jewish self-determination in our ancestral homeland.

While acknowledging the complexities and challenges that arose with the establishment of the modern State of Israel, including the war that followed and the corresponding displacement of Palestinian Arabs, it’s crucial to understand Israel’s creation in the context of this long historical arc of Jewish connection to the land. The State of Israel today continues to serve as a safe haven for Jews worldwide, fulfilling its role as the national home of the Jewish people.

Ancient Origins

The Jewish connection to the land of Israel, spanning thousands of years back to the Iron Age Israelites, is deeply rooted in history and religious tradition. We can explore this enduring relationship through crucial historical moments and archaeological finds.

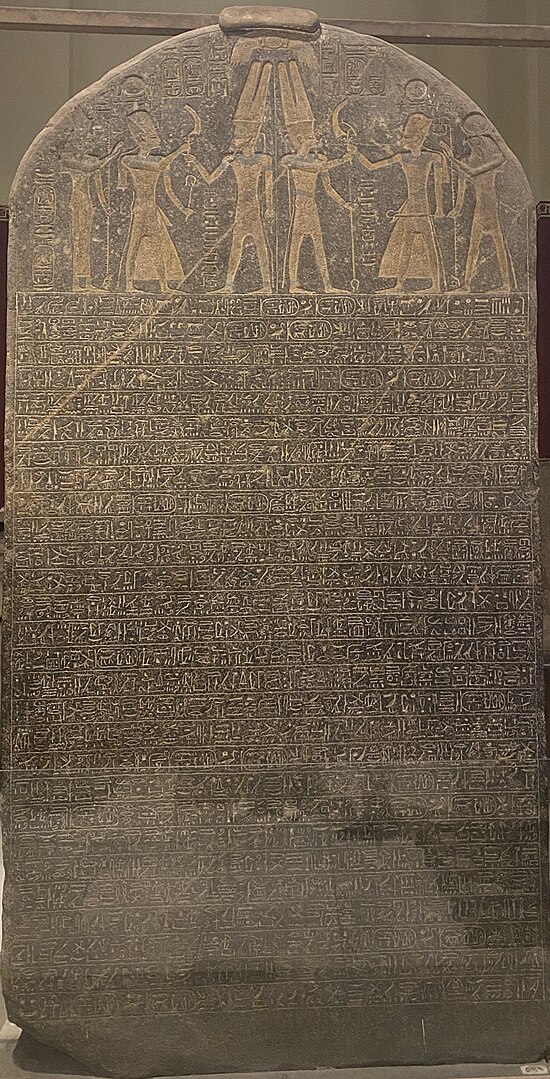

The first historical record of the name “Israel” referring to what was then the nomadic Israelite tribe can be found on the Ancient Egyptian Merneptah Stele inscribed in the 13th Century BCE as part of a military narrative of the pharaoh Merneptah of a campaign in Canaan2, it states:

“…The princes are prostrate, saying: “Shalom” …Israel is laid waste—bare of seed…”3

Undeniably, however, in some form, Israel’s “seed” was not extinguished. The Torah, with its last book, Deuteronomy, written by what is believed to be an Israelite living in the kingdom of Judah, Jerusalem, in the 8th Century and revised by another in the 6th, testifies to the formation of ancient Israel, a kingdom under Saul, David, and Solomon, establishing a sovereign Jewish presence in the land. King Saul was the first monarch of the United Kingdom of Israel around 1020 BCE. King David solidified this connection by making Jerusalem Israel’s political and spiritual capital.

The exact archaeological truth in this original account of the United Israelite Monarchy remains a matter of historical debate. However, discoveries such as the Tel Dan Stele, which references the “House of David,” affirm the historical reality of David’s dynasty. At the same time, excavations at both Khirbet Qeiyafa and the City of David suggest a polity like this did exist in the 10th century BCE, even as some argue Davids’s kingdom was more nomadic and did not build cities4.

Israel and Judah

Despite the ongoing debate over the nature of the Kingdom of David, there is a long-understood historical record of its traditional successor states, Judah in the south, with its capital at Jerusalem5 since at least the 9th Century BCE and Israel in the north in the Galilee and Samaria in what is now the West Bank since the late 10th.

Northern Israelites of this period coalesced behind an oral tradition reflected in the stories of the modern Torah and the idea of G-d that Jews understand today. The foundations of what would become Judaism were not the only belief system, and some worshipped the Canaanite thunder deity Ba’al. The Torah suggests this was why the two states were at war in their early history, the Judahites believing the Kingdom of Israel to be sinful, but there is little historical evidence for this conflict.

The Neo-Assyrian Empire gradually conquered Israel at around 730 BCE. The Torah refers to a displacement, describing the traditional narrative of the ten lost tribes; the historical debate is varied, but the leading archaeologist Israel Finkelstein has suggested evidence that 40,000 (a fifth of the population of Israel) were deported from the tribes of Reuben, Gad, Manasseh, Ephraim and Naphtali.6

Judah remained an attested monarchy for the next 200 years, and the significance of Jerusalem as the spiritual centre for Jews cannot be overstated; traditionally, the city that was chosen by David, with the First Temple built around 960 BCE by his son Solomon. This became the central place of worship for the Jewish people and where the Jewish religion began to formalise.

The Babylonians

The surviving Judahite state fell to the Babylonians in the early 6th Century BCE, as the Neo Assyrians declined, leaving a power vacuum in the Levant between Egypt (to which Judah was then allied) and the Babylonians under Nebuchadnezzar II. He would lay siege to Jerusalem in 587 BCE, destroying it and exiling a quarter of the population to Babylon in a series of deportations as was Babylonian policy in the lands they conquered; in addition, many of the elite were held captive, as Babylon annexed ancient Judah.7

The Persian Period

Only 39 years after Nebuchadnezzar II’s conquest, the Neo-Babylonian empire would be decisively destroyed by the Achaemenid Persian Empire, marking the start of the Persian occupation of Judah as “Yehud Medinata” the Province of Judah.

Traditional biblical accounts in the book of Ezra describe Cyrus the Great as signing edicts permitting the Jews held in Babylon and wider Mesopotamia to return to Jerusalem and rebuild the temple of Solomon destroyed by the Babylonians8; this work was completed in 515 BCE. The degree to which Jews migrated back to Judah occurred is the subject of debate. Some historians maintain it was a trickle over time and not the subject of Decree9, while others point to an ancient Clay Cylinder referencing the Persian restoration of sanctuaries and repatriation of deportees as evidence. However, this does not mention Jews, Judah or Jerusalem; it is more likely that Jews of their own initiative began to return to Judah.10

Many Jews also never left Mesopotamia after the Babylonian exile; these communities spread around the Middle East, becoming the Iraqi, Persian, Georgian, Bukharan and Mountain Jewish communities; in the present day, the vast majority of these ancestral Jewish populations, the “golah” or dispersal, have migrated to the state of Israel.

Under the Persians, the Jewish Priesthood and family line were well-resourced and well-documented; the Persians accepted and, in some instances, subsidised Jewish ritual, pilgrimage and worship in Jerusalem. Judah continued to operate as a temple state of the Persian Empire11

While the early scriptures, oral traditions, temple worship, Psalms and the Sabbath were all ancient parts of Jewish tradition, It was under the Persians that the Jewish people could first develop the notions and tenants of Modern Judaism of the written law and where Monotheism was popularised. Judaism in the Persian province of Yahud thrived over the next 200 years before the Persians fell to Alexander the Great. In the summer of 332 BCE12

Hellenistic Judaism

During the initial years of the Greek period, Judaism flourished much like it had done under the Persians under the temple and the high priest in Jerusalem. The successor empires to Alexanders in the Near East, Ptolemy in Egypt and the Seleucids in Syria would trade hands over Judea five times before Ptolemy secured it in 301 BCE; the instability in this period limited the influences of Greek or Hellenic culture and left the high priest and the priestly aristocracy a significant degree of autonomy over internal affairs.13

It was also during this period that the oldest known reference to a Synagogue can be found in Egypt on a dedication and a papyrus dated to 218 BCE, showing how Judaism had already expanded beyond the temple service with the structures we know today.15

Between 221 and 201 BCE, the Seleucids invaded and took control of Judea, ruling over the next 67 years, wavering between first affirming the autonomy of Jews under their ancestral laws under Antiochus III to the most violent repression of Jews since the Babylonians, the attempted complete Hellenisation and suppression of Judaism under Antiochus IV.

Antiochus, fearing rebellion among the Priestly class, banned Judaism and took direct control over the temple, rededicating it to an amalgam of Greek paganism and Judaism. These actions caused an actual rebellion in the Jewish Maccabean revolt in 168 BCE under Judah Maccabee against the Seleucids and the Hellenised Jews who backed them.16

The Maccabees, over the next four years, would wage a guerrilla war on the Seleucids and build an army large enough to reassert control over Jerusalem, reaffirming ancestral Judaism and again dedicating the temple to the Monotheistic faith in 164 BCE in what is now celebrated as the Jewish festival of Hannukah.

The Seleucids, however, would continue to war with the Maccabees, retaking Jerusalem in 160 BCE, installing Hellenised Jews and taking hostages to ensure suppression. However, the Maccabees continued to maintain an autonomous state in the countryside.

The Hasmonean Kingdom

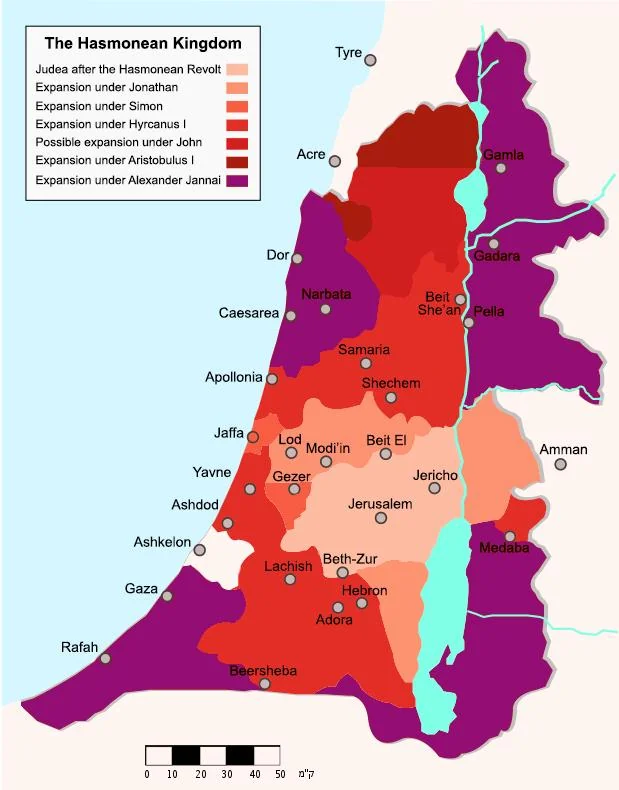

Through deal-making between the Maccabee Jonathan I and rivals in an internal Seleucid conflict, the Maccabees could eventually secure an autonomous Jewish state in Judea again in 152 BCE with the temple under Jewish control and Jonathan I named as High Priest and General under Alexander I still notionally under the Seleucid Empire.

There would be more betrayals as Jonathan I was eventually trapped and executed with his brother Simon, securing complete exemption from Seleucid taxes before finally repelling a Seleucid army in 139 BCE.

This would mark the beginning of what would eventually become the truly independent Jewish Hasmonean Kingdom over Judea for the first time since the original Kingdom of Judah, with Simon elected High Priest and Nasi by the Jewish people and securing alliance with Rome.17

During this period, Rabbinic Judaism began to develop as religious matters were settled by the Zugot. These pairs of rabbinic scholars led the spiritual and legislative chamber of the Sanhedrin, starting at the time of the Maccabean revolt, forming the foundation of the modern religion.

The Hasmonean Kingdom became so in 104 BCE when Astrobulus I declared himself king, expanding into some of the territories of the crumbling Seleucid Empire. Including Samaria, Idumea, Galilee and Ituria.18 it’s noted the Hasmoneans, despite being Priests of the tribe of Levi, were not in line for the Kingdom or the High Priesthood under the laws of Jewish law and nevertheless presided over an autonomous Jewish state with its administration and coinage and nine rulers recognised by the Roman Senate over 103 years.19

The Hasmonean Kingdom lost independence in 63 BCE when the Roman General Pompey was invited to resolve a dispute over the Hasmonean crown; the General laid siege to Jerusalem, killing 12,000 and invading the Holy of Holies and striping the Crown from the Hasmoneans while leaving them with the High Priesthood, the administration was broken, and Judea was left reliant on Roman administration in Syria ending independent Jewish statehood in the Levant for 2000 years20

The Second Temple (Herodian) Era

During the Judea of the Roman period, Rabbinic Judaism was formalised as we now know it. Herod the Great, a son of Nabatean converts, ascended to power as a Roman client king and began renovating and expanding the Second Temple around 20 BCE, a project designed to restore the Temple’s physical grandeur and solidify Herod’s political and religious influence over Judea.

Herod’s political manoeuvring was brutal; he eliminated the male Hasmonean line before marrying a Hasmonean princess, blending the old Hasmonean heritage with his new Herodian rule, a strategic move to secure his legitimacy and consolidate power.

From 4 BCE to 66 CE, Jews experienced a period of relative autonomy under Roman rule. This local governance allowed for some self-regulation and cultural preservation, contributing significantly to the development of Rabbinic Judaism. The first year of the Great Jewish Revolt against Rome in 66/67 CE was marked by the minting of a rare silver coin inscribed with “holy Jerusalem,” symbolising Jewish aspirations for independence and the sacred status of the city.

The revolt, however, culminated in tragedy. In 70 CE, the Romans under Nero destroyed the Second Temple, a catastrophic event that marked a significant turning point in Jewish history. Over 12,0000 were killed.

The loss of the Temple (marked by Jews today as Tisha B’Av, the 9th of the month of Av, a fast day) profoundly impacted Judaism. It changed forever the ability to perform the temple rituals, shifting the Jewish people towards Rabbinic Judaism.

The Bar Kokhba Revolt

The Bar Kokhba Revolt was a significant yet tragic attempt by the Jewish people to reclaim their autonomy from Roman rule.

The inscribed coin, variably also translated as “second year to the freedom of Israel“, signifies the rebels’ determination and hope for Jewish independence.

This period reflected the strong nationalistic and religious fervour driving the Jewish resistance. However, in 135 CE, the revolt was brutally crushed by the Romans, leading to severe consequences for the Jewish population. The defeat resulted in significant Jewish casualties and displacement, marking the beginning of the Jewish diaspora as many Jews were expelled from Judea.

‘Syria Palaestina’

Following the suppression of the Bar Kokhba Revolt, the Romans took further steps to erase Jewish connections to the land. In 136 CE, Emperor Hadrian expelled Jews from Jerusalem, intensifying the diaspora and scattering Jewish communities across the Roman Empire.

In a broader strategy to punish and suppress any resurgence of Jewish nationalism, the Romans renamed Judea to “Syria Palaestina.” After the biblical enemy of the ancient Hebrews, the Philistines. The Romans ethnically cleansed large numbers of Jews and denied the Jewish ancestral home its name, erasing it from public consciousness.

Post Roman Exile

Despite these efforts, Jewish presence and cultural heritage persisted in the land. The Byzantine period (324-638 CE) is particularly significant, as it saw a continuous Jewish presence in the area despite the hardships imposed by foreign rulers. Archaeological finds, such as mosaic tesserae and church structure fragments on the Temple Mount, provide evidence of this enduring presence.

During the Byzantine period, Jews managed to maintain a community despite being a minority under Christian rule. Jewish life centred around the synagogue, which served as a place of worship and a communal hub for social and educational activities. Jewish scholars continued to study and teach the Torah, ensuring the preservation and transmission of religious traditions and cultural practices.

The arrival of Islam in the 7th century brought significant changes to the region. The Muslim conquests led to the establishment of the Umayyad and, later, the Abbasid caliphates, which controlled much of the Middle East, including Palestine. Under Islamic rule, Jews were generally treated as dhimmi, a sort of second-class status for Muslim monotheists allowed to practice their religion but subject to social restrictions, taxes and legal restrictions. Despite these limitations, Jewish communities often thrived economically and culturally. The Islamic Golden Age, particularly in cities like Baghdad, saw Jewish scholars contributing to philosophy, medicine, and science.

While in what is now Israel, particularly in Jerusalem and Safed, the Jewish community persisted to the present day through the Middle Ages; many Jews fleeing persecution would journey back to Israel to these populations.

Conclusion

Judaism in the diaspora has always viewed the loss of the temple and the ancestral desire to return to Zion, or Jerusalem, the ancestral home of the Jewish people, as a core tenant of modern faith and the broader Jewish culture, the millennia of history of Judah and Israel is testament to the deep Jewish connection to what is now the state of Israel and has always informed the Jewish desire to be a nation with our autonomy once again. This desire, compounded by centuries of persecution in Europe, is the heart of Zionism, the preservation of the Jewish people in the Jewish ancestral homeland, having outlasted every occupier in our history.

Footnotes

- ↩ https://www.worldhistory.org/image/8465/dead-sea-scroll-28-from-qumran/

- ↩ https://ancientegyptonline.co.uk/sisrael/

- ↩ Hasel, Michael (2008). “Merenptah’s reference to Israel: critical issues for the origin of Israel”. In Hess, Richard S.; Klingbeil, Gerald A.; Ray, Paul J. (eds.). Critical Issues in Early Israelite History. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-598-4.

- ↩ https://www.haaretz.com/archaeology/2021-07-26/ty-article/was-king-david-a-nomad-new-theory-sparks-storm-in-archaeology/0000017f-f90d-d887-a7ff-f9edcc580000

- ↩ https://www.haaretz.com/archaeology/2016-01-04/ty-article/what-the-hezekiah-seal-proves-jerusalem-status/0000017f-ef78-df98-a5ff-effd370b0000

- ↩ Finkelstein, Israel; Silberman, Neil Asher (2002) The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology’s New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts, Simon & Schuster

- ↩ Finkelstein, Israel; Silberman, Neil Asher (2001). The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology’s New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts. Simon and Schuster.

- ↩ https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/babylonian-exile/

- ↩ Grabbe, Lester L. (2004). A History of the Jews and Judaism in the Second Temple Period: Yehud — A History of the Persian Province of Judah v. 1

- ↩ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cyrus_Cylinder

- ↩ https://www.britannica.com/topic/Temple-of-Jerusalem

- ↩ https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/palestine-in-the-hellenistic-age/

- ↩ ibid

- ↩ ibid

- ↩ https://web.archive.org/web/20201118094345/https://www.pohick.org/sts/faqs.html#What%20is%20the%20earliest%20evidence%20for%20ancient%20synagogues

- ↩ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maccabean_Revolt

- ↩ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maccabean_Revolt

- ↩ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hasmonean_dynasty

- ↩ https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/the-hasmonean-dynasty/

- ↩ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siege_of_Jerusalem_(63_BC)

Leave a Reply