The History of Jewish Life in Israel

Three thousand years of unbroken connection—from ancient Israelites to modern statehood. Explore the archaeological evidence, historical records, and enduring legacy that shaped the Jewish homeland.

Beyond the Myths: Understanding Israel’s Ancient Roots

The establishment of Israel in 1948 was never, as so frequently framed, simply a response to the Holocaust. Or, indeed, a European colonial enterprise. Instead, Israel and the notion of Zionism can be viewed as the culmination of a clear line of Jewish history stretching back to the Iron Age.

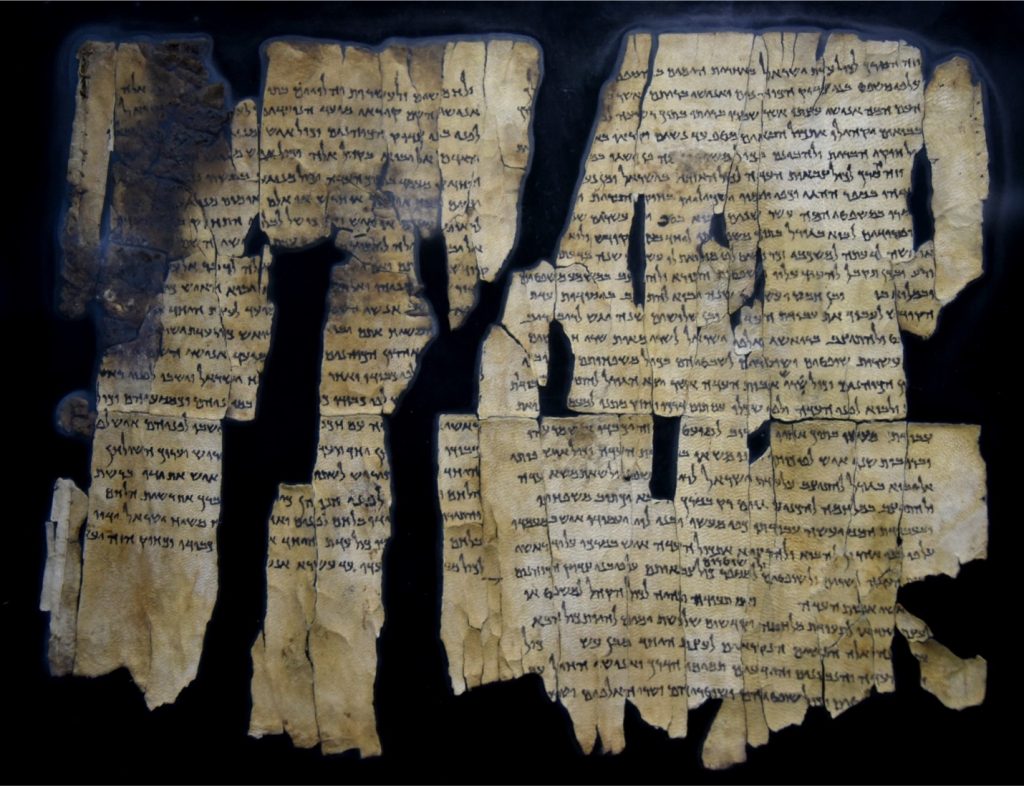

The stories of the Torah might be mythological, with the early books consisting of what most would call a founding myth. Still, these narratives are undeniably ancient—proof, especially through the ancient biblical texts found in the Dead Sea Scrolls, of their age, the people that revered them, the place where they did so, and the area where the stories were written. That place was roughly the same as the modern-day State of Israel; those people were the Israelites who became the Jewish people.

This is why Jewish people, quite apart from sharing a common Levantine genetic heritage, also share a sense of belonging to the nation of Israel—of being one people, one extended family or tribe. The State of Israel represents the fulfilment of a long-standing aspiration for Jewish self-determination in our ancestral homeland.

Dead Sea Scroll 28a (1Q28a)

Found in Cave 1 at Qumran, dated between 408 BCE to 318 CE. These ancient manuscripts provide irrefutable evidence of Jewish presence and religious practice in the land of Israel over two millennia ago.

Journey Through 3,000 Years of Jewish History

Key Historical Periods

The historical timeline of Jewish life in Israel spans several critical periods, each representing a chapter in the enduring connection between the Jewish people and their ancestral homeland. This connection has persisted through conquest, exile, and return.

Ancient Origins

13th Century BCE – 587 BCE

From the first historical mention of Israel on the Merneptah Stele to the United Kingdom under David and Solomon, and the divided kingdoms of Israel and Judah. This period established Jerusalem as the Jewish spiritual center.

Second Temple Period

539 BCE – 70 CE

Spanning Persian, Hellenistic, Hasmonean, and Roman rule, this era saw the rebuilding of the Temple, the development of Rabbinic Judaism, and ultimately the destruction of the Second Temple by the Romans.

Diaspora & Presence

70 CE – 1882 CE

Despite exile and foreign rule under Byzantine, Islamic, Crusader, Mamluk, and Ottoman empires, Jewish communities maintained a continuous presence in Jerusalem, Safed, Tiberias, and Hebron throughout this period.

Modern Israel

1882 – Present

Beginning with the First Aliyah and the rise of modern Zionism under Theodor Herzl, through the British Mandate period, to the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948 and its subsequent development as the Jewish national home.

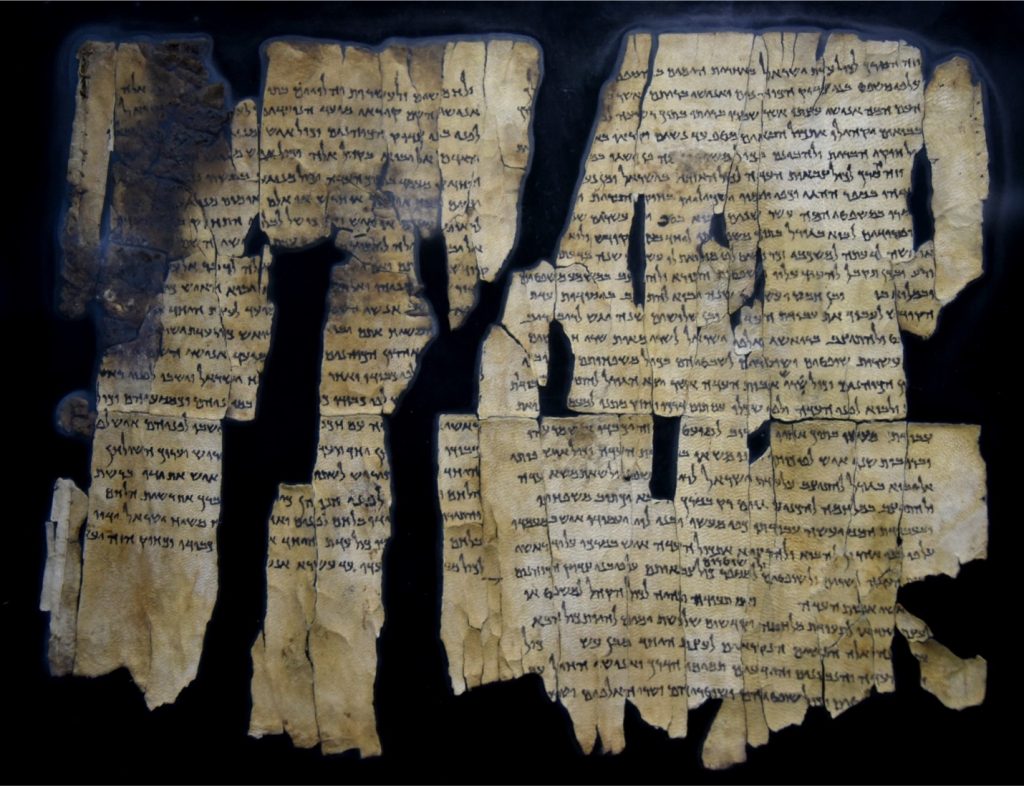

The First Record of Israel

The Jewish connection to the land of Israel, spanning thousands of years back to the Iron Age Israelites, is deeply rooted in history and religious tradition. We can explore this enduring relationship through crucial historical moments and archaeological finds.

The first historical record of the name “Israel” referring to what was then the nomadic Israelite tribe can be found on the Ancient Egyptian Merneptah Stele, inscribed in the 13th Century BCE as part of a military narrative of the pharaoh Merneptah’s campaign in Canaan.

Israel is laid waste—bare of seed…”

Undeniably, however, in some form, Israel’s “seed” was not extinguished. The Torah, with its last book Deuteronomy written by what is believed to be an Israelite living in the kingdom of Judah in the 8th Century and revised by another in the 6th, testifies to the formation of ancient Israel—a kingdom under Saul, David, and Solomon, establishing a sovereign Jewish presence in the land.

King Saul was the first monarch of the United Kingdom of Israel around 1020 BCE. King David solidified this connection by making Jerusalem Israel’s political and spiritual capital. Discoveries such as the Tel Dan Stele, which references the “House of David,” affirm the historical reality of David’s dynasty.

Israel and Judah: Two Kingdoms, One People

Despite the ongoing debate over the nature of the Kingdom of David, there is a long-understood historical record of its traditional successor states: Judah in the south with its capital at Jerusalem since at least the 9th Century BCE, and Israel in the north in the Galilee and Samaria since the late 10th century.

Northern Israelites of this period coalesced behind an oral tradition reflected in the stories of the modern Torah and the idea of G-d that Jews understand today. The foundations of what would become Judaism were not the only belief system—some worshipped the Canaanite thunder deity Ba’al.

The Neo-Assyrian Empire gradually conquered Israel around 730 BCE. The Torah refers to a displacement, describing the traditional narrative of the ten lost tribes. Leading archaeologist Israel Finkelstein has suggested evidence that 40,000 people—a fifth of the population—were deported from the tribes of Reuben, Gad, Manasseh, Ephraim and Naphtali.

Judah remained an attested monarchy for the next 200 years. The significance of Jerusalem as the spiritual centre for Jews cannot be overstated—traditionally the city chosen by David, with the First Temple built around 960 BCE by his son Solomon. This became the central place of worship for the Jewish people and where the Jewish religion began to formalise.

The Destruction and Exile

The surviving Judahite state fell to the Babylonians in the early 6th Century BCE. Nebuchadnezzar II laid siege to Jerusalem in 587 BCE, destroying it and exiling a quarter of the population to Babylon in a series of deportations. Many of the elite were held captive as Babylon annexed ancient Judah.

Only 39 years after this conquest, the Neo-Babylonian empire would be decisively destroyed by the Achaemenid Persian Empire, marking the start of the Persian occupation of Judah as “Yehud Medinata”—the Province of Judah.

Return and Rebuilding

Traditional biblical accounts describe Cyrus the Great signing edicts permitting Jews held in Babylon to return to Jerusalem and rebuild Solomon’s Temple—work completed in 515 BCE.

Under the Persians, the Jewish Priesthood was well-resourced; the Persians subsidised Jewish ritual, pilgrimage and worship in Jerusalem. It was under Persian rule that the Jewish people developed the notions and tenets of Modern Judaism—the written law—and where Monotheism was popularised.

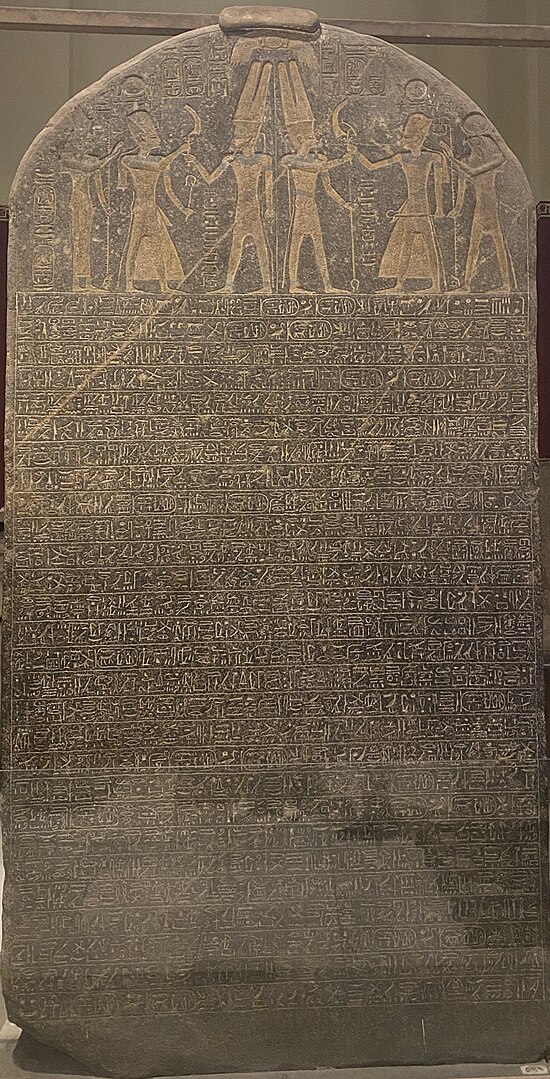

The Maccabean Revolt and Hasmonean Kingdom

After Alexander the Great conquered Persia in 332 BCE, Judaism initially flourished under Greek rule. The successor empires—Ptolemy in Egypt and the Seleucids in Syria—traded control over Judea five times. It was during this period that the oldest known reference to a Synagogue appears in Egypt, dated to 218 BCE.

Between 221 and 201 BCE, the Seleucids took control, wavering between affirming Jewish autonomy under Antiochus III to the most violent repression since the Babylonians under Antiochus IV. Fearing rebellion, Antiochus banned Judaism and took direct control over the Temple, rededicating it to an amalgam of Greek paganism.

These actions sparked the Maccabean revolt in 168 BCE under Judah Maccabee. Over four years, the Maccabees waged guerrilla war and reasserted control over Jerusalem, rededicating the Temple to the Monotheistic faith in 164 BCE—now celebrated as the Jewish festival of Hanukkah.

Through deal-making and alliances, the Maccabees eventually established the truly independent Jewish Hasmonean Kingdom—the first since the original Kingdom of Judah. During this period, Rabbinic Judaism began to develop through the Zugot, pairs of scholars who led the Sanhedrin, forming the foundation of the modern religion.

The Hasmonean Kingdom presided over an autonomous Jewish state with its own administration and coinage, with nine rulers recognised by the Roman Senate over 103 years—until independence was lost in 63 BCE when the Roman General Pompey laid siege to Jerusalem.

Hasmonean Coin of John Hyrcanus I

135–104 BCE. Inscribed in Paleo-Hebrew: “Yehohanan the High Priest and head of the Council of the Jews” — tangible evidence of Jewish self-governance.

The Second Temple Era: Tragedy and Transformation

Coin of the Jewish Revolt (66–70 CE)

Inscribed with “Holy Jerusalem” in Paleo Hebrew. Found in the Judean desert, this 2,000-year-old silver coin symbolised Jewish aspirations for independence. Image Credit: Israeli Antiquities Authority.

During the Roman period, Rabbinic Judaism was formalised as we now know it. Herod the Great, a son of Nabatean converts, ascended to power as a Roman client king and began renovating and expanding the Second Temple around 20 BCE—a project designed to restore the Temple’s grandeur and solidify his political and religious influence.

From 4 BCE to 66 CE, Jews experienced a period of relative autonomy under Roman rule, contributing significantly to the development of Rabbinic Judaism. But tension mounted, culminating in the Great Jewish Revolt of 66 CE.

The revolt ended in catastrophe. In 70 CE, the Romans under Nero destroyed the Second Temple—a turning point in Jewish history. Over 12,000 were killed. The loss of the Temple, marked by Jews today as Tisha B’Av (the 9th of Av, a fast day), profoundly impacted Judaism, shifting the people towards Rabbinic Judaism and away from Temple-centred worship.

The Bar Kokhba Revolt (132–135 CE) was the last significant attempt to reclaim autonomy. Coins inscribed “year two of the liberation of Israel” signified the rebels’ determination. But in 135 CE, the revolt was brutally crushed, resulting in massive Jewish casualties and displacement—marking the intensification of the Jewish diaspora.

Following suppression, Emperor Hadrian expelled Jews from Jerusalem and renamed Judea to “Syria Palaestina”—after the Philistines, biblical enemies of the Hebrews—in a deliberate attempt to erase Jewish connection to the land.

Persistence Through Exile: The Unbroken Chain

Despite Roman efforts to erase Jewish connection to the land, Jewish presence and cultural heritage persisted. The Byzantine period (324–638 CE) saw continuous Jewish presence despite hardships under Christian rule. Jewish life centred around the synagogue—a place of worship and communal hub for social and educational activities.

Byzantine Period (324–638 CE)

Jews maintained communities as a minority under Christian rule. Scholars continued studying and teaching Torah, preserving religious traditions and cultural practices through the synagogue system.

Islamic Rule (638–1099 CE)

Under the Umayyad and Abbasid caliphates, Jews were treated as dhimmi—allowed to practice their religion but subject to restrictions. Despite limitations, Jewish communities often thrived economically and culturally.

The Four Holy Cities

Throughout the Middle Ages, Jewish communities persisted in Jerusalem, Safed, Tiberias, and Hebron. Many Jews fleeing persecution in Europe journeyed back to Israel to join these populations.

The Heart of Zionism

Judaism in the diaspora has always viewed the loss of the Temple and the ancestral desire to return to Zion—Jerusalem, the ancestral home of the Jewish people—as a core tenet of faith. The millennia of history of Judah and Israel testify to the deep Jewish connection to what is now the State of Israel.

This desire, compounded by centuries of persecution, is the heart of Zionism: the preservation of the Jewish people in their ancestral homeland, having outlasted every occupier throughout history. While acknowledging the complexities that arose with modern Israel’s establishment, it’s crucial to understand Israel’s creation in the context of this long historical arc of Jewish connection to the land.